I consider “Marighella” to be perhaps the most important project I have ever done, both for my personal involvement and for political issues. It was very difficult to have to wait so long to see the movie on screen because of political reasons in addition to the pandemic.

Marighella is a very important film for the days we are going through. I’m sure the movie will be successful even if box office is a little affected by the pandemic.

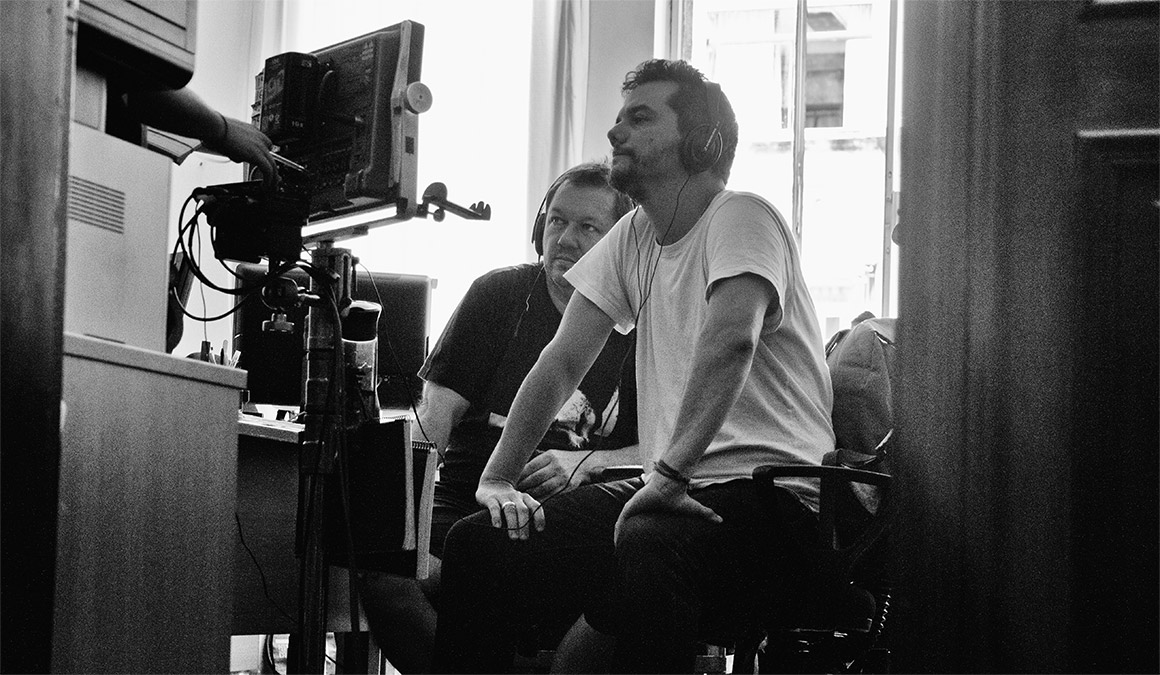

Despite already having a huge amount of set experience, this is Wagner Moura’s first feature film as a director. All of our conversations prior to the project were fundamental to understanding what Wagner wanted.

Photos: Ariela Bueno, Fabio Bouzas and Fernanda Frazão

I consider “Marighella” to be perhaps the most important project I have ever done, both for my personal involvement and for political issues. It was very difficult to have to wait so long to see the movie on screen because of political reasons in addition to the pandemic.

Marighella is a very important film for the days we are going through. I’m sure the movie will be successful even if box office is a little affected by the pandemic.

Despite already having a huge amount of set experience, this is Wagner Moura’s first feature film as a director. All of our conversations prior to the project were fundamental to understanding what Wagner wanted.

Photos: Ariela Bueno, Fabio Bouzas and Fernanda Frazão

Ariel Schvartzman

CAMERA AND ACTION

Mini Bio

Adrian Teijido started getting involved with photography when he was still a teenager, encouraged by his parents who worked in the audiovisual industry. After learning experiences in the processing laboratory of the Lasar Segall Museum and in the film “Pixote: A Lei do Mais Fraco” (1981), as an intern for the photographer Rodolfo Sanchez, he began his professional career in cinema and in the advertising world. He worked as a camera assistant for five years at Última Filmes with director and photographer Ronaldo Moreira. Over 40 years, he signed the cinematography of films such as “O Palhaço” (2011), “Gonzaga: De Pai pra Filho” (2012), “Elis” (2016), “Sergio” (2020) and “Medida Provisória” (2020), as well as television series such as “Filhos do Carnaval” (2006), “A Pedra do Reino” (2007), “Narcos” (2015-2019), “Irmandade” (2019) and “Dom” (2021) , among other projects. He was eight times winner of the ABC Award (Brazilian Association of Cinematography), three times winner of the Grand Prix of Brazilian Cinema and received the Kikito trophy at the Gramado Film Festival with “Um Homem Só” (2016), among other awards for cinematography. He is a member of ABC and was president of the association between 2016 and 2017. He was born in Buenos Aires in 1963 and moved with his family to Brazil at the age of four.