After a period of decline brought about by the consolidation of the very advanced technologies for capturing digital images, the idea of shooting on film gradually reappears. The Super 8, 16mm and 35mm film stocks have already been starting to roll on a new movement that is here to stay both in advertising productions and in experimentalist cinema. In Brazil, it is already possible to find rental options for analog cameras and importing film stock, in addition to professionals who can go through all the steps of the development and telecine processes, carried out mainly abroad.

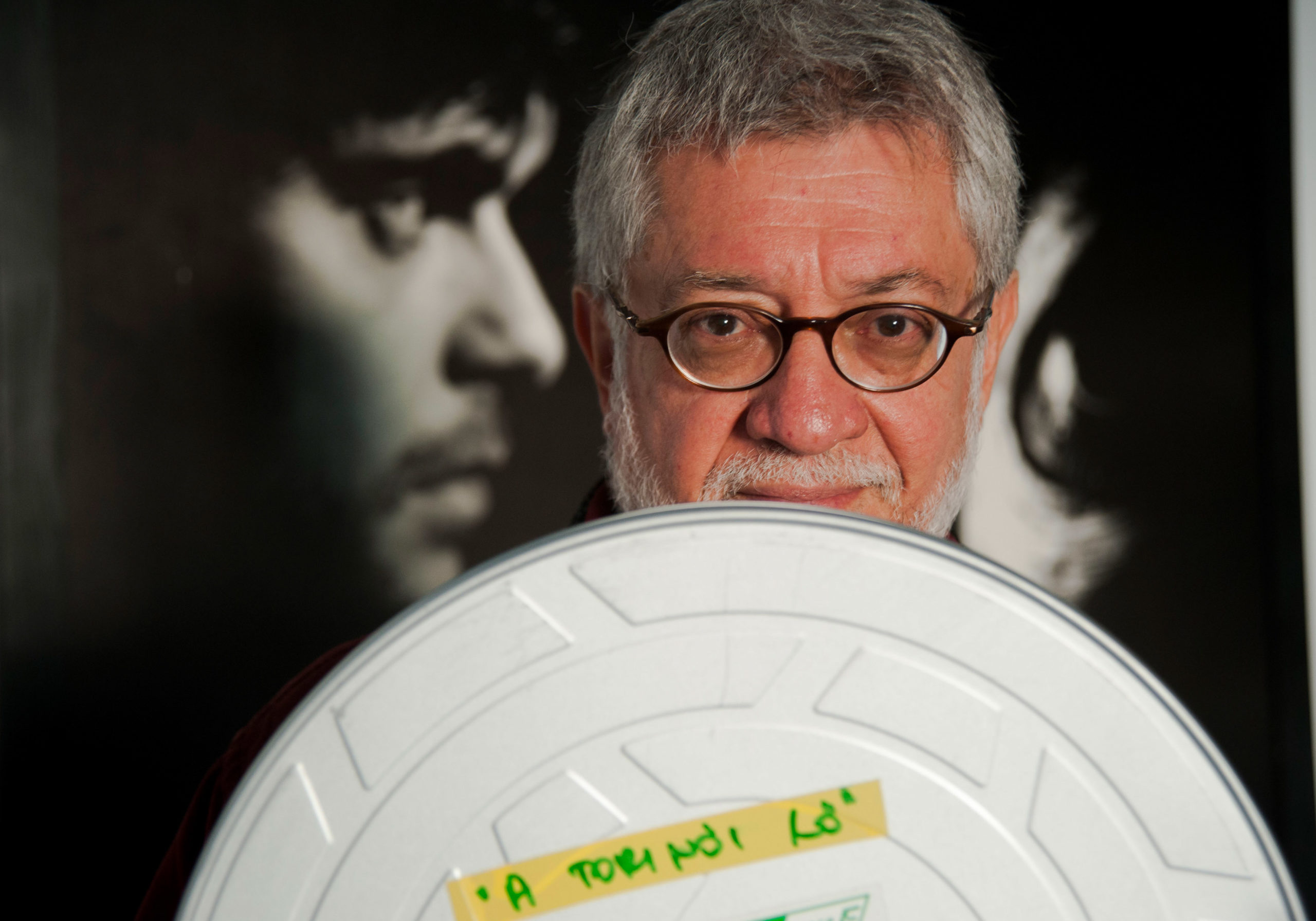

“We have gone so far as to build software to produce digital images, but still have a faithful appearance to film”, reflects Walter Carvalho, consecrated as one of the main cinematographers in Brazil, who wrote an article on the subject especially for Iris (full text is at the end of this page).

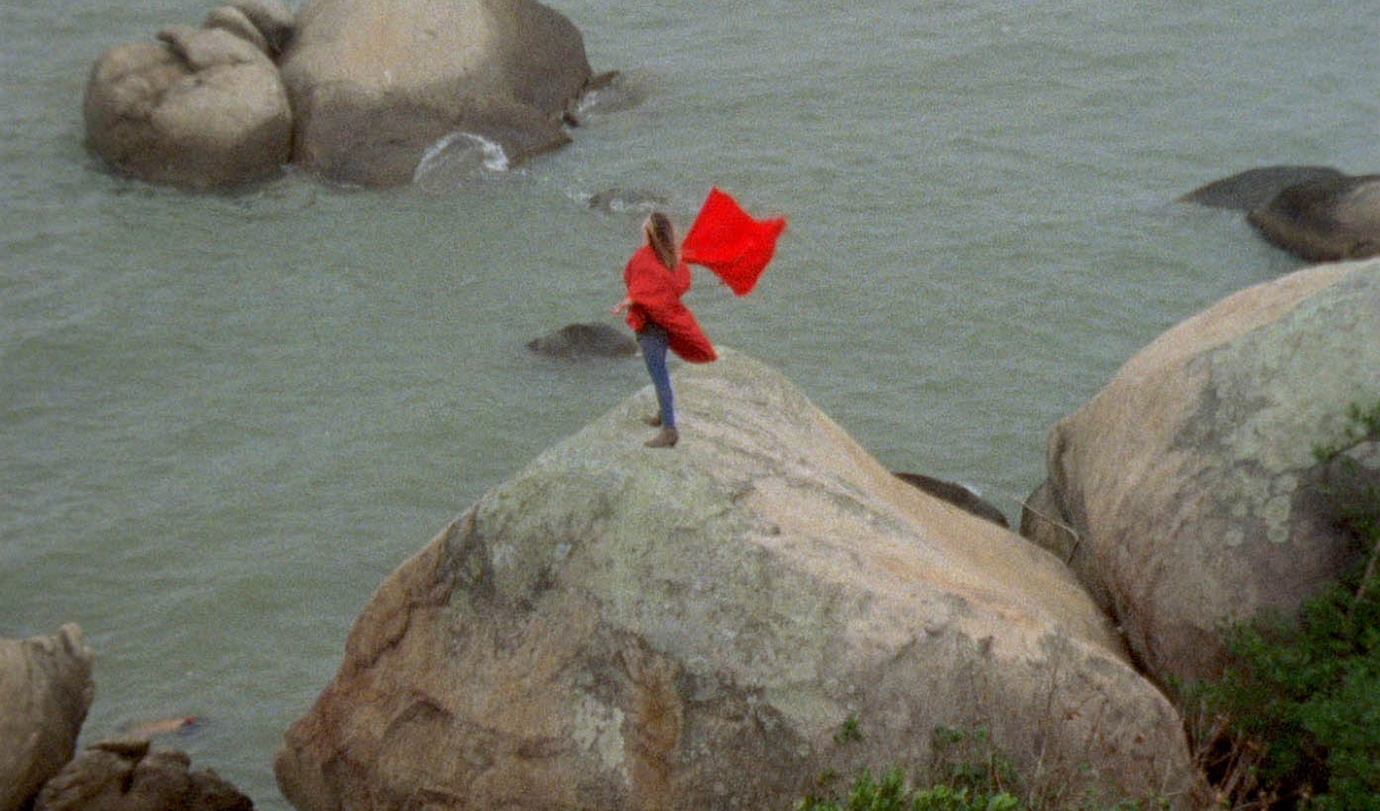

“With new technologies, I don’t drive, I’m driven. If, on one hand, we meet the demand for content and distribution with stunning speed, on the other hand our craft as a cinematographer has lost its epic meaning”, compares Walter, who in 2021 celebrates 50 years of cinematography and photographed classics like Sargento Getúlio (1983), Central do Brasil (1998) and Lavoura Arcaica (2001). One of his most beautiful works is Terra Estrangeira (1995), shot on 16mm in Black & White.

“When you look at a ‘good image’ built by new technologies, the expression almost always comes: “it looks like film”. The photography used to take place inside the camera, in the sealed black box and then in the dark during processing. Now it is built outside of it” , differentiates Walter, who has already completely embraced digital cameras.

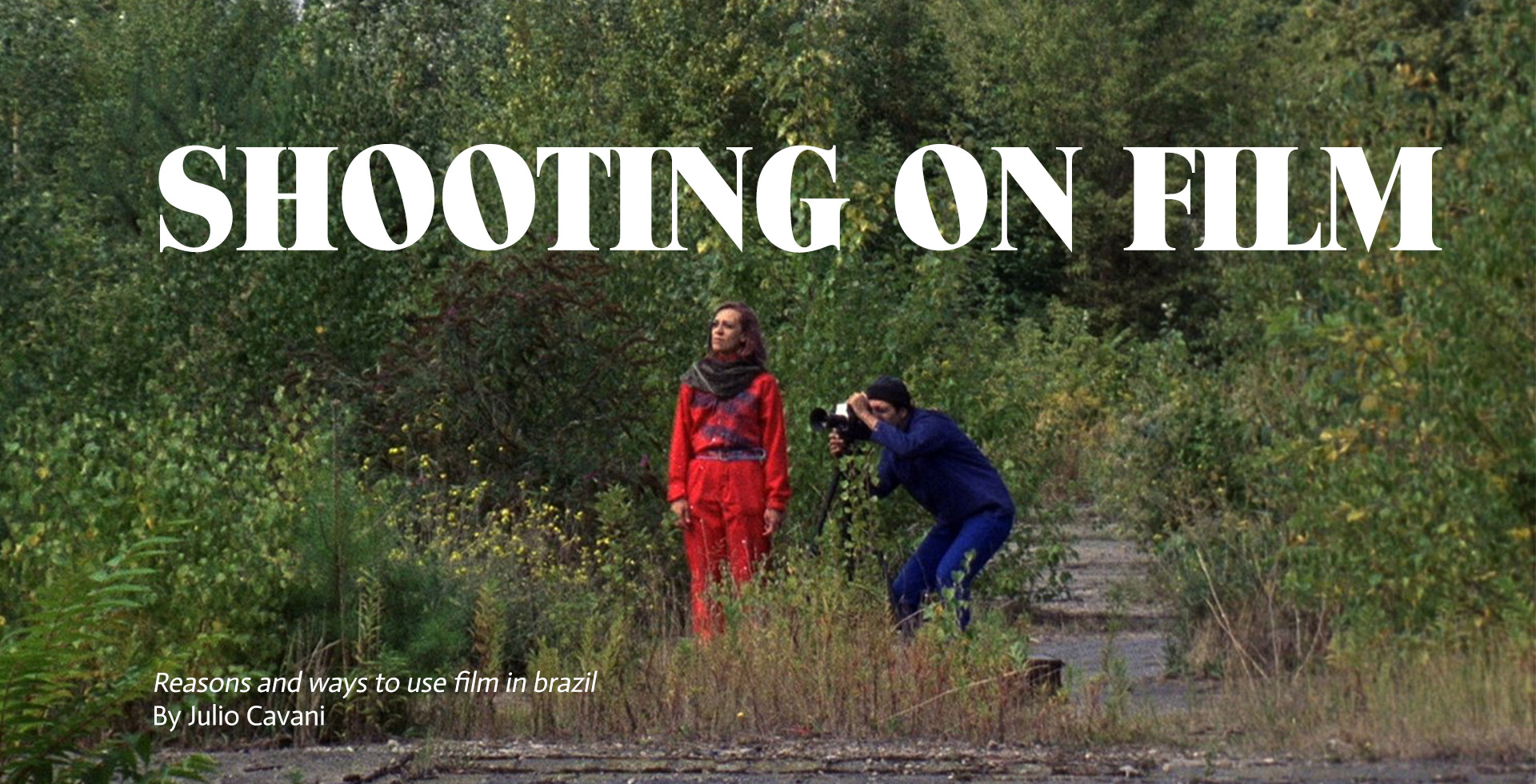

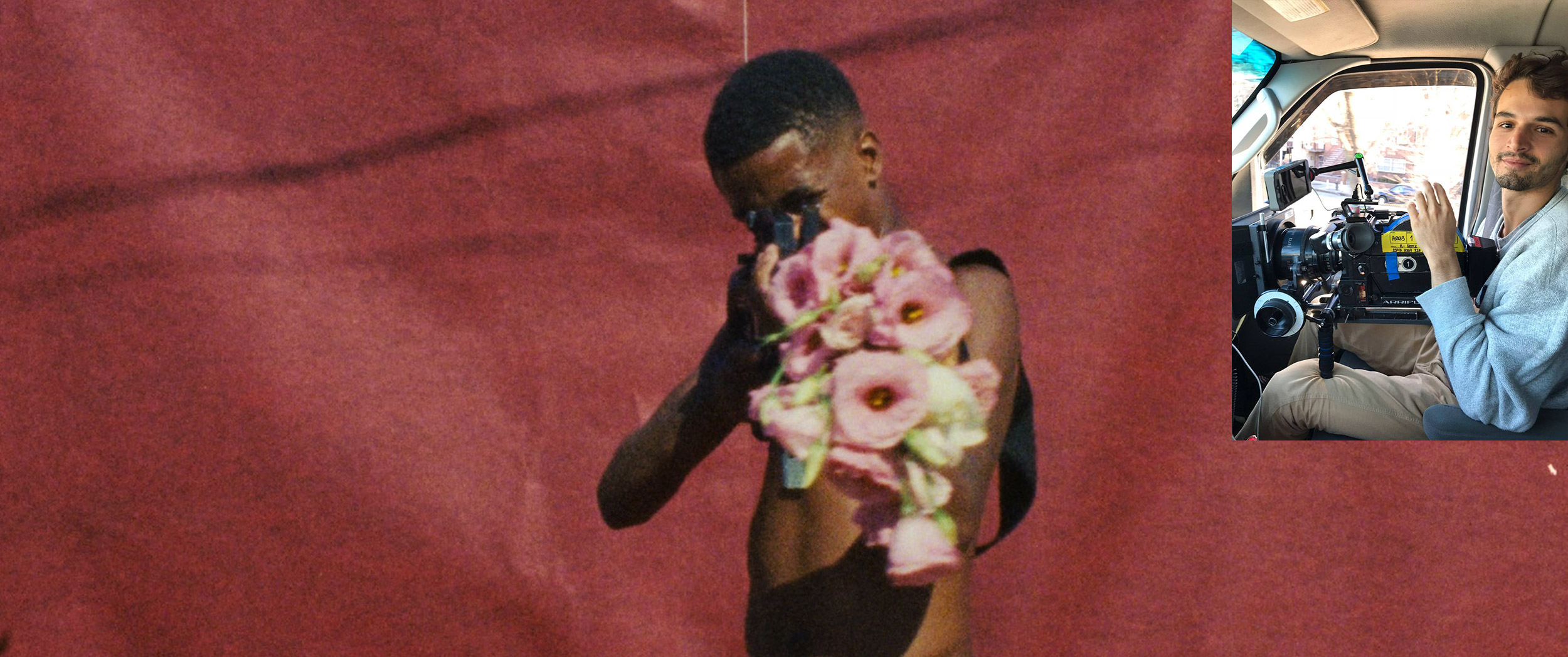

Frames of the films “Xarpi”, “Desmond” and “Ciclos” (Marechal’s music video), directed by Breno Moreira

“I shoot all my personal films on film,” attests director and photographer Breno Moreira. He is proof that this dream is possible, but he admits that he got that opportunity thanks to some privileges: “I was lucky to be in New York, where my sister lives, when a friend invited me to test an old SR2 camera, with 700 meters of negatives for us to use. We went to Queens and made the short ‘108th St’, a documentary about street dancers.” Since then, he hasn’t stopped and has been able to use 16mm films regularly to shoot documentaries, shorts, music videos and commercials for brands such as Puma, Nike and C&A.

In 2021, Breno will release his first feature film, Jambalaia, a documentary about the situation of the residents of a group of buildings that was demolished in Rio de Janeiro, shot on 16mm. For him, “most people still avoid it a lot, but it can be economically viable and quick to shoot on film if you plan everything in detail. This forces me to always be more focused and think carefully about what will be filmed. The mechanics are different, it’s something that affects the behavior of the entire crew. Everyone lives in that moment and in the end they want to take pictures next to the camera.”

In private, Breno always carries a Canon Scoopic and usually films his daughter’s daily life, a habit that gave him ideas for a new personal documentary, not yet released. “Shooting on film is a delight, but I understand it as a tool and not only aesthetics” admits Breno, who prefers not to base his choice on more technical arguments: “I went to a lecture by Vittorio Storaro and he said he considers photographers who insist on film are outdated, as if they were going backwards.”

Frame from the music video Ciclos (cinematography by JP Garcia) and picture of Breno Moreira with an Aaton camera

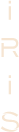

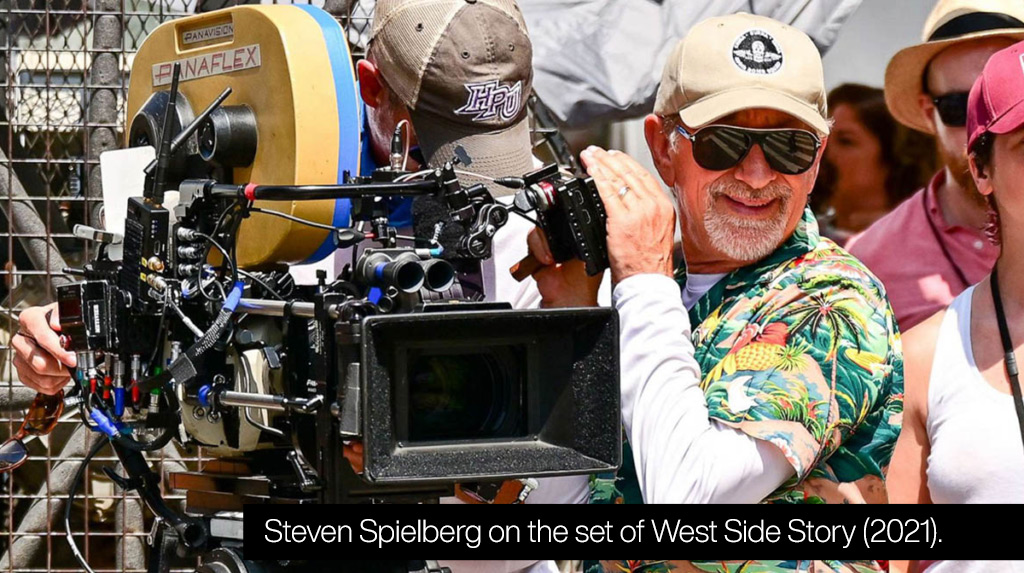

In North American cinema, among the main releases in recent years, there is a good portion of feature films shot on film. Steven Spielberg, for example, used 35mm film to shoot his new version of the musical West Side Story, with cinematography by Janusz Kaminski and scheduled to be released in 2021. The superproduction Wonder Woman 1984, released in theaters by DC Entertainment at the end of 2020, was filmed with 35mm and 65mm Arri, Panavision and IMAX cameras, directed by filmmaker Patty Jenkins and cinematography by Matthew Jensen. 007: No Time to Die (2021), new film in the James Bond franchise, was captured on 35mm and 65mm by DoP Linus Sandgren.

Sound of Metal shot in 35mm.

A very emblematic case is Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), by Quentin Tarantino, which has scenes shot with four different gauges. Robert Richardson, director of photography, used Kodak 35mm color, 35mm Black & White, 16mm and Super 8 films. The filmmaker never adhered to the digital format, and neither did Christopher Nolan, who also always shoots on film and who directed Tenet (2020), shot on 65mm negatives with Panavision, Arri and IMAX cameras, by cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema.

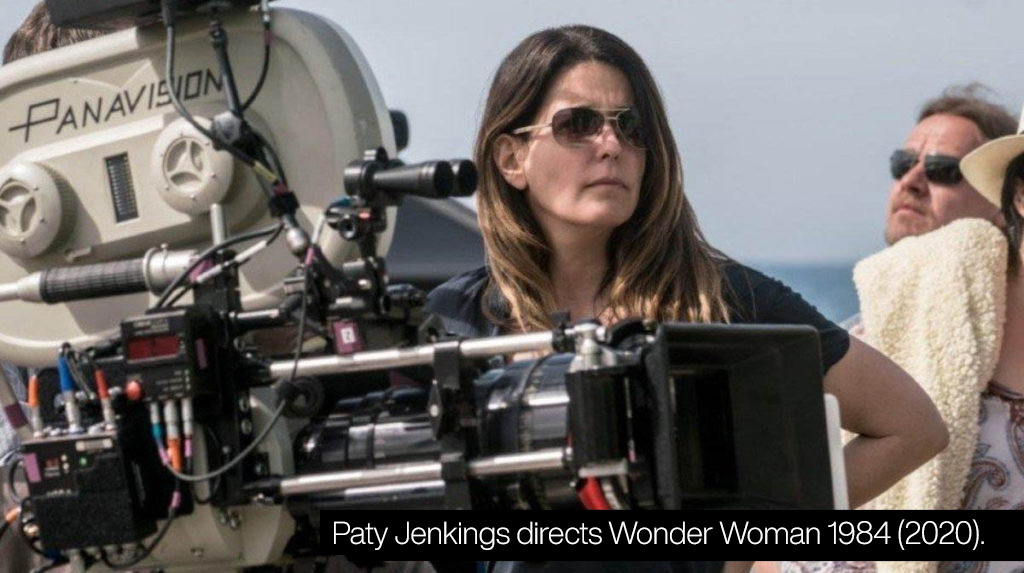

Among the 2021 Oscar nominees, The Sound of Silence, The United States vs. Billie Holiday and Blood Detachment were shot or have film sequences, in addition to Tenet. In 2020, among the nominees for Best Film and Best Cinematography, 52% were shot on film.

Los Conductos (2020)

Paulo Menezes/ A Metamorfose dos Pássaros, de Catarina Vasconcelos/ Primeira Idade, Portugal, 2020

At the Berlin Film Festival in 2020, four of the winners were shot on 16mm: the Colombian Los Conductos, the Portuguese A Metamorfose dos Pássaros, the Serbian Otac and the North American Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Always. At the 2021 Berlinale, the same gauge was used in the Georgia’s What Do We See When We Look at the Sky, winner of the Fipresci (International Federation of Film Critics) award.

Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series used both 35mm and 16mm film developed at Cinelab London.

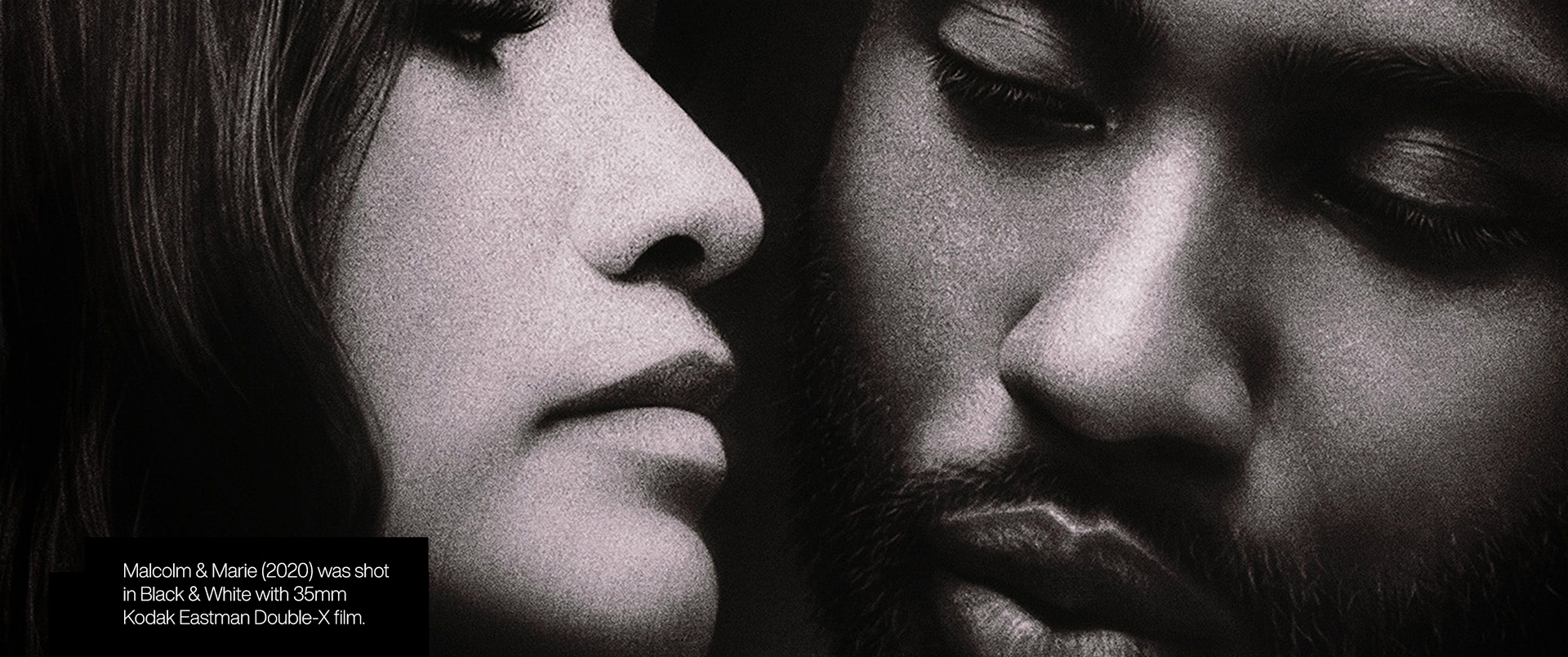

Film also continues to be present in television productions and films released on streaming platforms. This is the case, for example, with the series Westworld, Succession, both by HBO, and Small Axe, by BBC (available on Globoplay), and the feature films The Devil All the Time (35mm) , Malcolm & Marie (shot on B&W 35mm) and Da 5 Bloods (16mm and digital), released by Netflix in 2020 and 2021. Some use 16mm for period scenes set in the past. Others feel that the grain generates an expressionist effect. Grain texture can also activate references and memories in the viewer’s sub-conscious.

Antonio Campos films The Devil All the Time (2020) in 35mm.

Kodak’s official website has a page which is always updated with new movies, series, music videos and commercials shot on film:

https://www.kodak.com/en/motion/page/shot-on-film

At least two Brazilian companies have cameras available to rent, of different brands and models, ready to run. “Between 2018 and 2019, before the pandemic, the consumption of negatives in Brazilian productions reached an average of one can per week”, evaluates Nestor Grun, from the MAC rental company. According to him, that number was 50 times lower a decade ago, but there has been a sudden resurgence of interest in film over the past four years. In his perception, right before the pandemic, the production of music videos was consolidated as the largest consumer of film in Brazil, mainly in 16mm and Super 8, while the advertising market also adopted a lot of 35mm celluloid.

MAC has the largest number of rental cameras (four 35mm and three 16mm) in São Paulo, but you can also find some 35mm units at JKL. Brands like Arri, Panavision and Aaton stopped making this type of equipment more than ten years ago, but the models that were last launched (and older ones) still work perfectly, and if there is good maintenance can work indefinitely.

Manufacturers realized that the reuse of used ones is already enough to meet the demand of those who still choose to shoot on analog film in the digital age, also due to the fact that some specific parts are still manufactured for replacement.

To purchase negatives, it is necessary to import from abroad. The buying process can be done independently, through online purchases or in person while traveling, but it is also possible to order the films through companies such as Runner, an official authorized importer of Kodak, which formally performs the entire process in an official manner and can offer lower prices for working with a greater volume of demand under special tax collection conditions.

The development should preferably be done in specialized companies, which offer the digitized material in 2K, 4K, 6K or 8K files, using advanced scanning technologies. In Brazil, the best digitalization equipment is at Cinecolor Digital, in São Paulo, which scans and telecines 35mm and 16mm, but does not develop the films. Abroad, there are large labs still active, mainly in cities like Los Angeles, New York and London. It is also possible to find informal Brazilian 16mm and Super 8 laboratories, like artistic collectives, based on experiments in filming projections, without the same stability (and speed of service) offered by professional technicians with more modern equipment.

Cameras used in Super 8 workshop offered by lab.irinto.lab

Based in São Paulo, lab.irinto.lab, linked to the Mundo em Foco collective, offers 16mm and Super 8 development and digitization services, in addition to selling film rolls with its own processing, such as “Fungi Films”, which they describe as “approximately 10km of expired cinema film, stored in dubious conditions that contributed to mold and uncontrollable effects on each roll”. They also offer courses, participate in festivals (especially the Super OFF and 1666) and have developed the negatives of Espera (2018), a feature film by director Cao Guimarães, and the film scenes of Ana. Sem Título (2020), by Lúcia Murat.

Marcos Ponts, from Maranhão, adopted the 16mm gauge in the feature film Chorando se Foi.

In Maranhão, filmmaker Marcos Ponts decided to shoot his first feature film on film. Produced in 2018, Chorando se Foi is currently being finalized, with cinematography by Roman Lechapelier, a French cinematographer based in São Luís at the time. The filmmaker guaranteed that shooting on 16mm was cheaper than using some of the new digital cameras, but he had to resort to a post lab in Romania to carry out the project.

“People laughed in my face and said I was crazy, that it would be impossible to shoot on film with the funds we had, but I’m driven by challenges and we overcame all risks. Chorando se Foi portrays the life of a projectionist. Rolls of film are present in several scenes. I tried to shoot with digital, but I didn’t like the results”, recalls Ponts: “If I could sum up the experience in two words, it would be sensuality and tension. It was very exciting to hear the noise of the camera, but we couldn’t run multiple takes and were relieved in the end.”

“The camera was an Arri SR2 with 16mm color film,” the director says. According to him, “at the time, renting a complete digital kit with Arri Alexa Mini for six weeks would be more expensive than using film. Today, this comparison would be different because of the high exchange rate between Brazilian reais (R$) and the US dollar. Through Roman, I met Rodrigo Ruiz, from Spain, who worked at Kodak and later bought a laboratory in Romania. He was an angel, he embraced my project and made it easy to reveal.”

Ivo Lopes Araújo operates a Bolex Rex 3 in a scene from the movie Tatuagem.

Director of photography Ivo Lopes Araújo is in the post-production process of the feature film Todas Vidas de Telma, predominantly shot on 16mm with a Bolex camera. He co-directed it with Antonio Luiz Mendes, renowned cinematographer of classics such as Das Tripas Coração (1982) and Ópera do Malandro (1986), who was a victim of COVID-19 at the age of 75 in December 2020. They decided to shoot on film the subjective images in the POV of the protagonist, the photo painter from Ceará, Telma Saraiva, who dedicated her life to painting over analog photographic portraits. The negatives were purchased at lab.irinto.lab and will be developed in New York.

“I believe in this alchemy of silver, which has a mystery and is almost a witchcraft”, observes Ivo about the filming and development process. “Shooting on film allows you to see the world optically, through the lens, and not through digitally processed viewfinders that emit electronic lights. You are really looking at people and spaces. The relationship between the body and the camera is also different, because the equipment takes another breath and doesn’t heat up like digital cameras,” compares Ivo, who admits that he has not yet had the opportunity to try out the new analog optical viewfinders developed for Arri digital cameras using mirror sets.

Previously, Ivo had the opportunity to shoot feature films such as Tatuagem (2013) and Ausência (2014) and short films such as Sem Coração (2014) and Solon (2016). “The appreciation of the take is much greater. It works very well for directors who do fewer takes, but it is contradictory for those who like to shoot a lot of material”, he ponders.

Formed by Brazilian artists Gustavo Jahn and Melissa Dulius, the collective Distruktur, based in Berlin since 2006, has already released two feature films shot on 16mm in the last five years, in addition to several short films. The most recent is the feature Oráculo, which participated in the Tiradentes Film Festival in 2021. They began experimenting with film when they were still living in Brazil, but in Germany they found more direct access to materials, equipment and laboratories.

Melissa Dulius and Gustavo Jahn in the films No Coração do Viajante, Muito Romântico and Oráculo.

“I started out shooting on film. I had video cameras at a very young age, which I used as a diary, but when I found the group I was going to make cinema with, it had to be on film. It was like that in Porto Alegre in 1999 with the collective Sendero, formed at the School of Librarianship and Communication at UFRGS (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul)“, recreates Melissa, who also experiments with projections, objects, installations and printed materials. “In Berlin, we joined the founding group of LaborBerlin, a cooperative film post-production laboratory, self-managed by the group. Since March 2020, I have been working at the Andec-Filmtechnik office, a reference in film development worldwide.”

In recent years, Distruktur has toured Brazil twice to develop projects and offer workshops that have been forming small groups, in different cities, of people interested in shooting with film, as if they were planting seeds. Over the past two decades, they have organized 20 courses in different parts of the world.

The duo of filmmakers Luciana Mazeto and Vinícius Lopes, from the production company Pátio Vazio, in Rio Grande do Sul, has directed a series of films on film, screened at major festivals such as and Rotterdam. The most recent is the documentary Os Olhos na Mata e O Gosto na Água“, a medium-length film selected in 2020 for the prestigious Visions du Réel festival, in Switzerland. In 2019, at the Cine Esquema Novo exhibition, in Porto Alegre, they curated a program of films shot on film produced at the LaborBerlin (Germany) and Worm.Filmwerkplaats (Netherlands) laboratories. At the same event, they offered a workshop on manual and experimental techniques for filming, developing and copying with 16mm, with materials such as Black & White negative and caffenol, an ecological solution that generates high-contrast images from ingredients found in supermarkets, as well as experiments with cyanotyping in artisanal emulsion.

“We had the opportunity to shoot our first short films on 16mm while in film school, and they were experiences that instigated us a lot. I had the opportunity to edit these films at the university’s Moviola, handling the material that we had physically captured”, Luciana remembers. For her, “the lab process, the uncertainties and the aesthetic possibilities that analog film provides can only be achieved using this format. The experience of filming, developing and experimenting with images using film is as rewarding as it is vast”. In Vinícius’ opinion, “there is something unique, singular in this whole process. Even if the film’s possibilities for aesthetic experimentation are extremely wide, it is the personal experience that changes most profoundly”.

The workshops offered by Luciana Mazeto and Vinícius Lopes involve filming and developing.

Images from the video clip of British band Black Market Karma filmed by Ivan Cordeiro from Pernambuco with a Super 8.

Ivan Cordeiro, from Pernambuco, who lives in Los Angeles, is a contemporary Super 8 activist and participates in international networks for exchanging information about the film. He is a member of the Californian Pro8mm lab and is used to acting as a connection for Brazilian filmmakers who need to develop negatives, digitize or restore old films. “The number one reason for the resurgence of interest in film is the advancement of new scanning technologies. The advent of 4k scanning, for example, brought a new possibility of beauty that emphasizes luminous intersections and grains”, he mentions. The quality, practicality and speed of the new machines that are available are a great attraction for new generations, in his opinion.

The new telecine scanners have boosted the resurgence of interest in shooting on film, but the recent rise in the dollar is a hindrance for Brazilians, says Ivan. “A three-minute Super 8 can costs $150, which currently means over R$750,” he calculates.

For personal use, Ivan has a Canon 1014, which sometimes needs to be repaired because of plastic engine, axis and gear parts. He warns that technicians who specialize in fixing cameras are slowly dying out, so it’s very important that people learn to fix it by themselves.

“Film has a captivating power and works as a testament to authenticity, something important to differentiate a film amidst so much visual information we receive today”, believes Ivan, who is one of the curators of the international film festival Curta 8, which has been happening for the past 17 years in Curitiba. He recently directed the music video for the song “Andrea’s Drum”, by British band Black Market Karma, released in January 2021 by the flower Power Records label, filmed in Super 8. During the pandemic, he developed the project “A Cameraman in Lockdown” and produced short films that can be viewed on his Vimeo and Youtube channels, which are published monthly. In 2020, he restored and digitized in 4K five rolls of images filmed by the RFSA on the São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro railways in 1971.

Lucyfer Kabra always adopts the Super 8 in experimentalist films such as the music video O Consolo das Antas.

Visual artist and musician Lúcifer Kabra is preparing to release the feature film Da Luz ao Vale, by Kino-Cobra Filmes, partially shot on Super 8, a format he uses in all of his films. “I use the Super 8 to be able to build images that can give new meaning to the relationship of the recording’s temporality. Assuming that every image is memory, film strengthens this perception”, he reflects.

For Lúcifer Kabra, “the film process is totally different when you know you have only 3 minutes to tell something. The camera’s trigger takes a magical proportion of the film’s burning, a unique event that you can only check out after a long journey of development and telecine. The possibilities of error can also generate unique results.” After Da Luz ao Vale, he will release another film, which is still in development, entirely shot in Super 8.

In an interview given to the North American website IndieWire in 2020, Steve Bellamy, president of Kodak’s Film and Entertainment division, said that the volume of negative production of all gauges, from 65mm to Super 8 has been increasing, including Black & White movies.

An issue that can also weigh on the budget is the transportation of negatives to laboratories abroad. “I don’t recommend sending by post”, warns Ivan Cordeiro, since a loss would be truly irreparable damage. With him, unfortunately, it already happened. Breno Moreira usually leaves everything planned and set with someone from the team, especially with cinematographers who live in England or the United States. It is possible to receive scanned images in less than a week, as the labs are fast, capable of working on multiple rolls simultaneously. “When I arrived at FotoKem with my few cans in hand, they were working simultaneously with Dunkirk, which had thousands of meters of film in process at that time,” recalls Breno. Christopher Nolan’s feature consumed 975 rolls of 65mm.

Until 2010, shooting on film in Brazil was still very common, both in cinema and in advertising, in miniseries and music videos. Quickly, digital cameras advanced on almost everything and movie theaters retired the old projectors. Gradually, however, several photographers are returning to analog filming, whether they are interested in more organic results, for an aesthetic choice or because they believe in the infinite flexibility of celluloid, which until now could not be considered outdated or less clear than the most advanced electronic technologies. Some argue that you shouldn’t compare, as they are really different languages.

I feel like Umberto Eco who said he was fascinated by errors.

It is from the error that I learn.

When I shot with film, as much as I tried to learn or master the technology of the time, there was a fascination with error in the sense that I was always searching. Certainty was based on inaccuracy.

I worked with a black box and with the darkness required for the film processing in the laboratory. I will never forget the moments lived in the lab rooms watching the first copies.

Adrenaline and emotion.

I wasn’t afraid of mistakes, I worried about the accuracy and I was always very skeptical about what was right.

The process was very rich and when I found myself full of certainties, everything lost its fun. The charm of discovery has always worked as a stimulus for my work.

With new technologies everything can be predicted or built in detail with minimal risk. Everything is instantaneous.

It’s technically possible to know how something will look before it’s ready, a paradox. If I already know what will happen as a result, because I can safely predict everything beforehand, the magic is gone. A hovering danger is good for the journey and above all for the result.

Film is not made with planning, film is made with cinema.

However, it is fascinating what new technologies offer us, despite being just tools. In the language of cinema there are neither standards nor manuals. It is alive, it is an invention contained in creation, that which can transcend.

To make Entreatos, by João Moreira Salles, for example, I used a digital camera by personal choice. I could have done it with film, but it would certainly be another film. Entreatos required a speed and mobility that traditional cinema equipment would not provide.

The photography first took place inside the camera, in the sealed black box and then in the dark during processing. Now it is built out of it. The image has become an equation that can solve all, or almost all, problems. This is fantastic.

But at the same time the digital process was developed to do what was done before. When looking at a “good image” built by new technologies, the expression almost always comes up: it looks like film.

We’ve reached the point of building software to produce digital images, but that looks faithful to film. It’s curious to say the least.

We cannot remain oblivious to the changes. Today, the wait for the laboratory process for the films could no longer be endured because the world is in a hurry.

In a flash you press a button and the image is made, and beautiful. But it is necessary to reflect on what is being done with the image on the planet today.

There is a clear exhaustion of the symbolic field. The excess and uncontrolled proliferation in the media make us overflow with banalities and disempowered images.

Here I transcribe the words of Italo Calvino that sum up this question very well:

“In our memory, thousands of fragments of images are deposited in successive strata, similar to a garbage dump, which makes it less and less likely that one of them will stand out.”

One of the most interesting features of cinema is that we do it to see what it looks like. With new technologies I don’t drive, I’m driven.

If, on one hand, we meet the demand for content and distribution with dizzying speed, on the other hand, the photographer has lost the epic sense of our craft.

The most important things for those who produce images are those displayed in front of the camera and above all what we intend with it.

But it is also necessary to allow the unrestrained desire of the eye. Because the camera, whatever it is, is an instrument that teaches us to see without a camera.

What matters is the wandering of the look.

Walter Carvalho

Lavoura Arcaica, Terra Estrangeira and Central do Brasil are among Walter Carvalho’s most emblematic cinematographic works shot on film.

Rasta Loc (Recife/ Fortaleza)

JKL (São Paulo)

lab.irinto.lab (São Paulo)

Runner Filmes

lab.irinto.lab (São Paulo)

Premises and equipment from Pro8mm, Cinecolor, Cinelab London, Fotokem and Metro laboratories.