JOCKEY

By Adolpho Veloso, abc

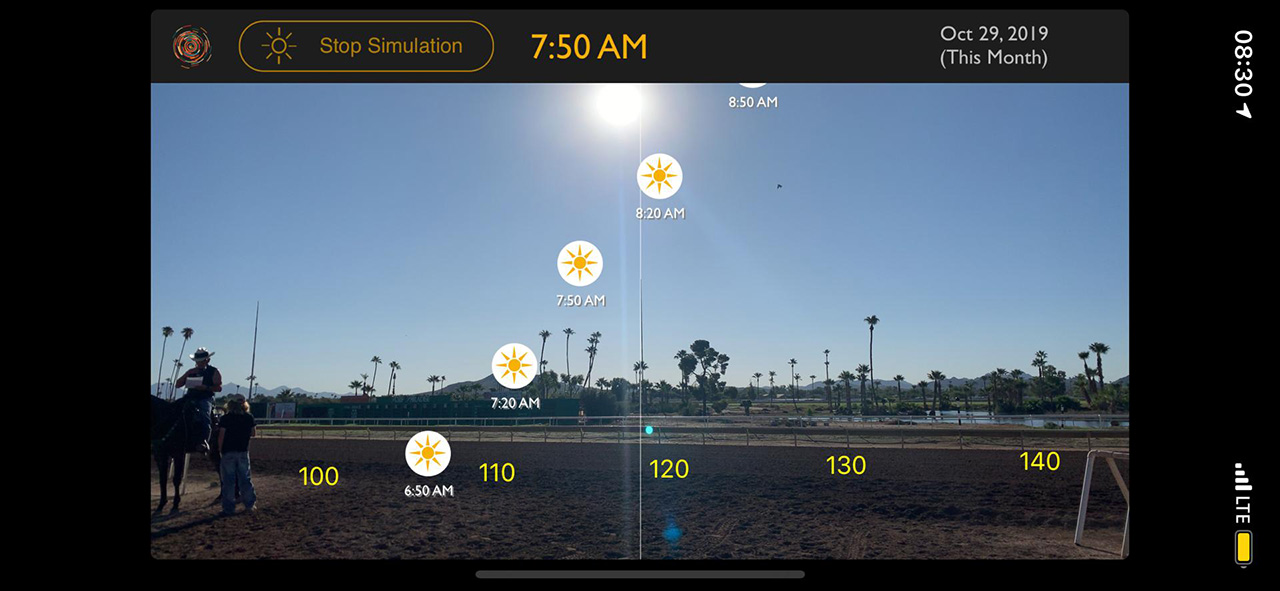

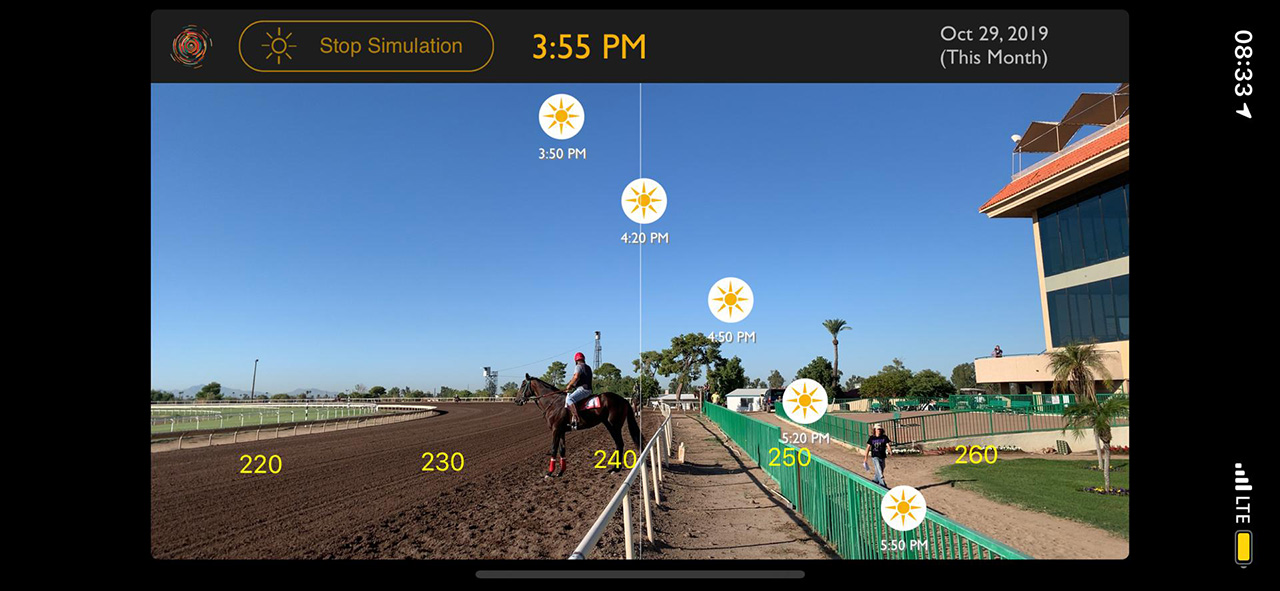

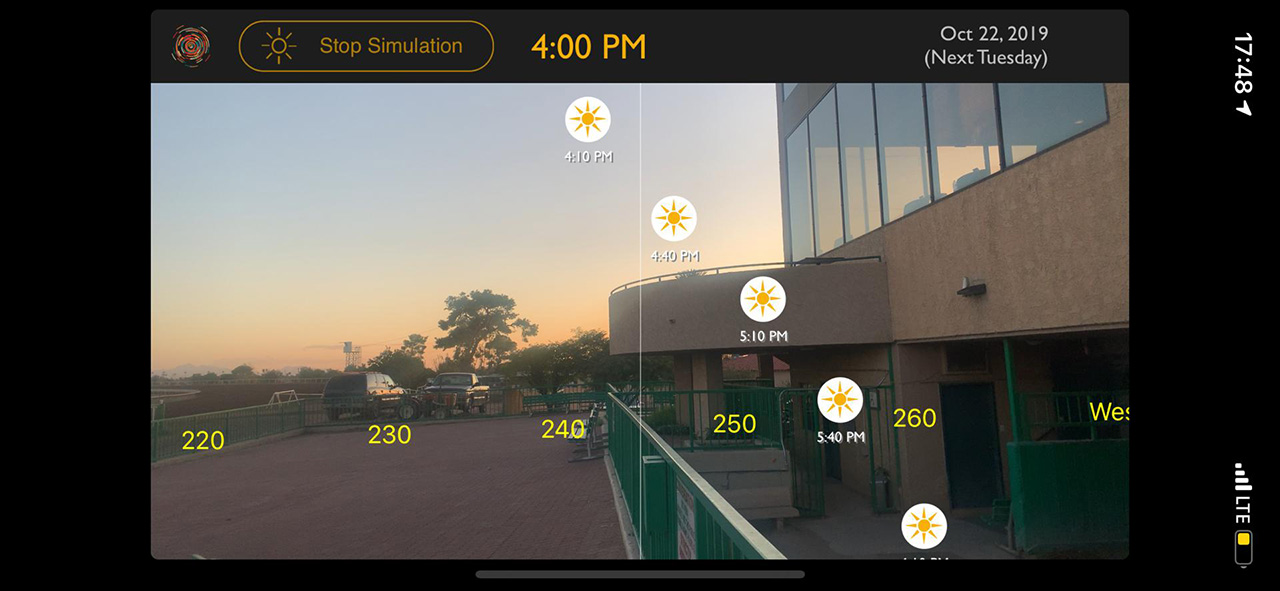

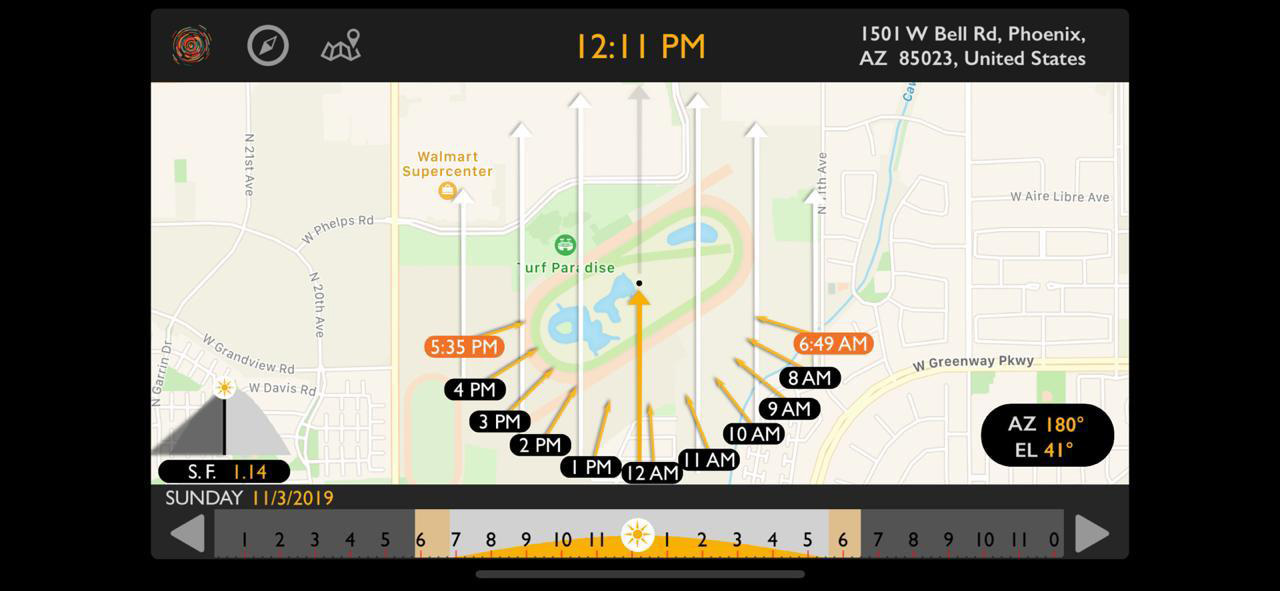

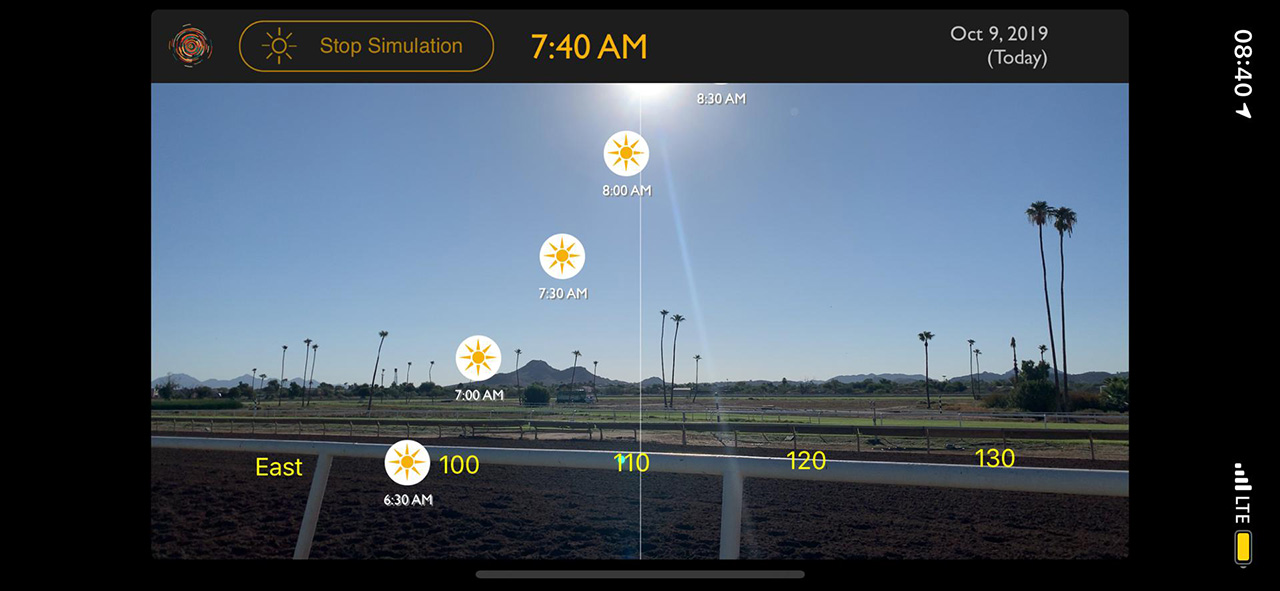

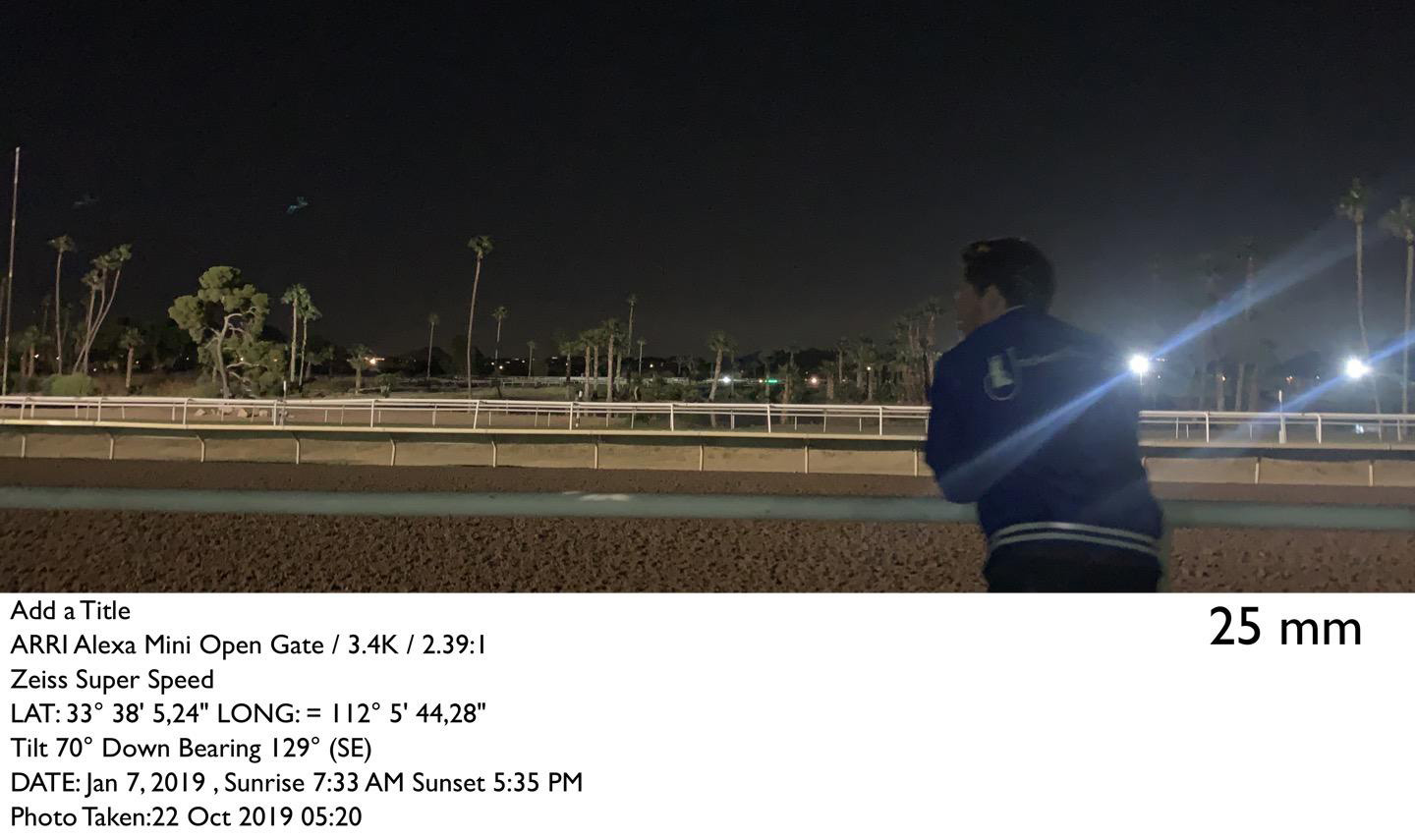

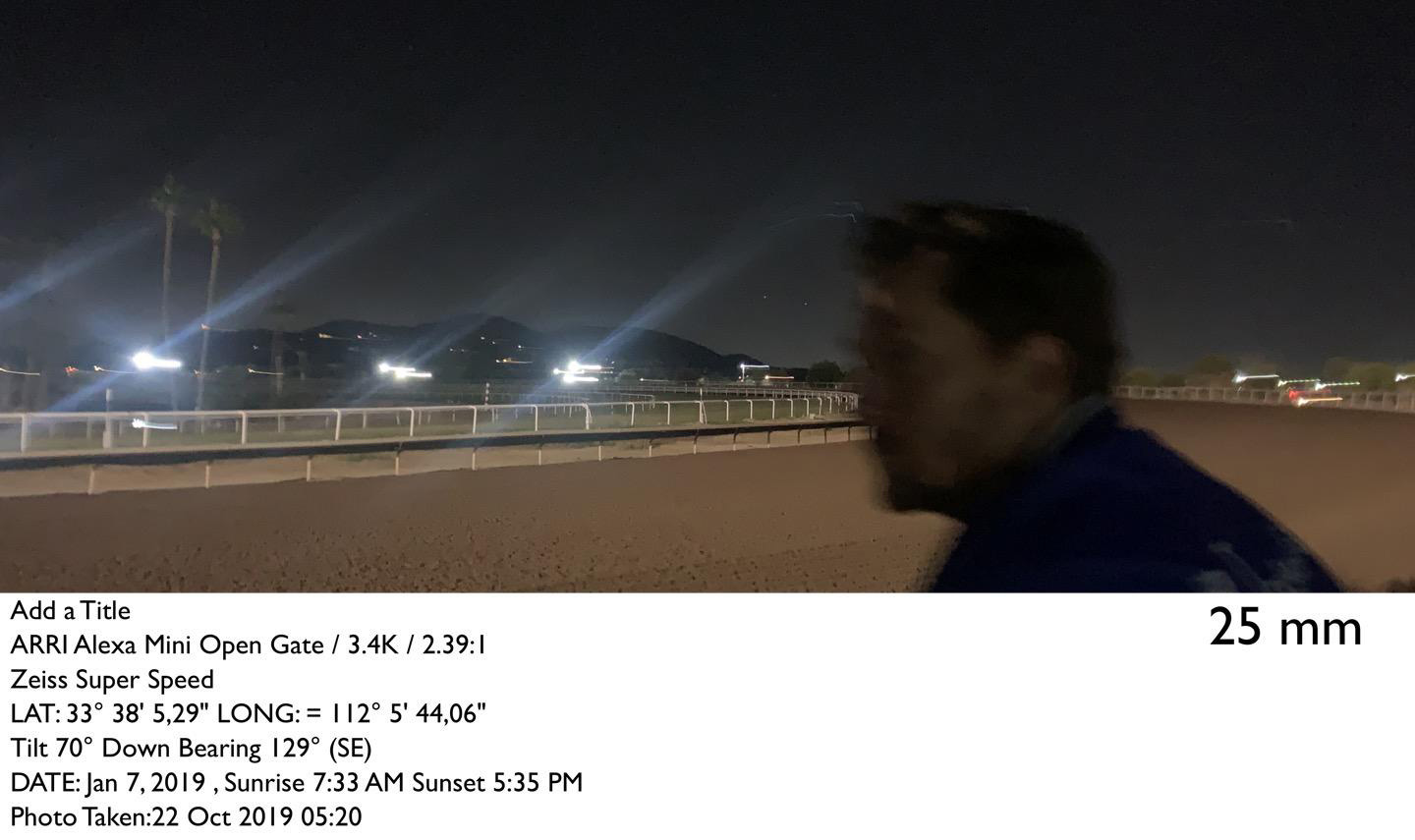

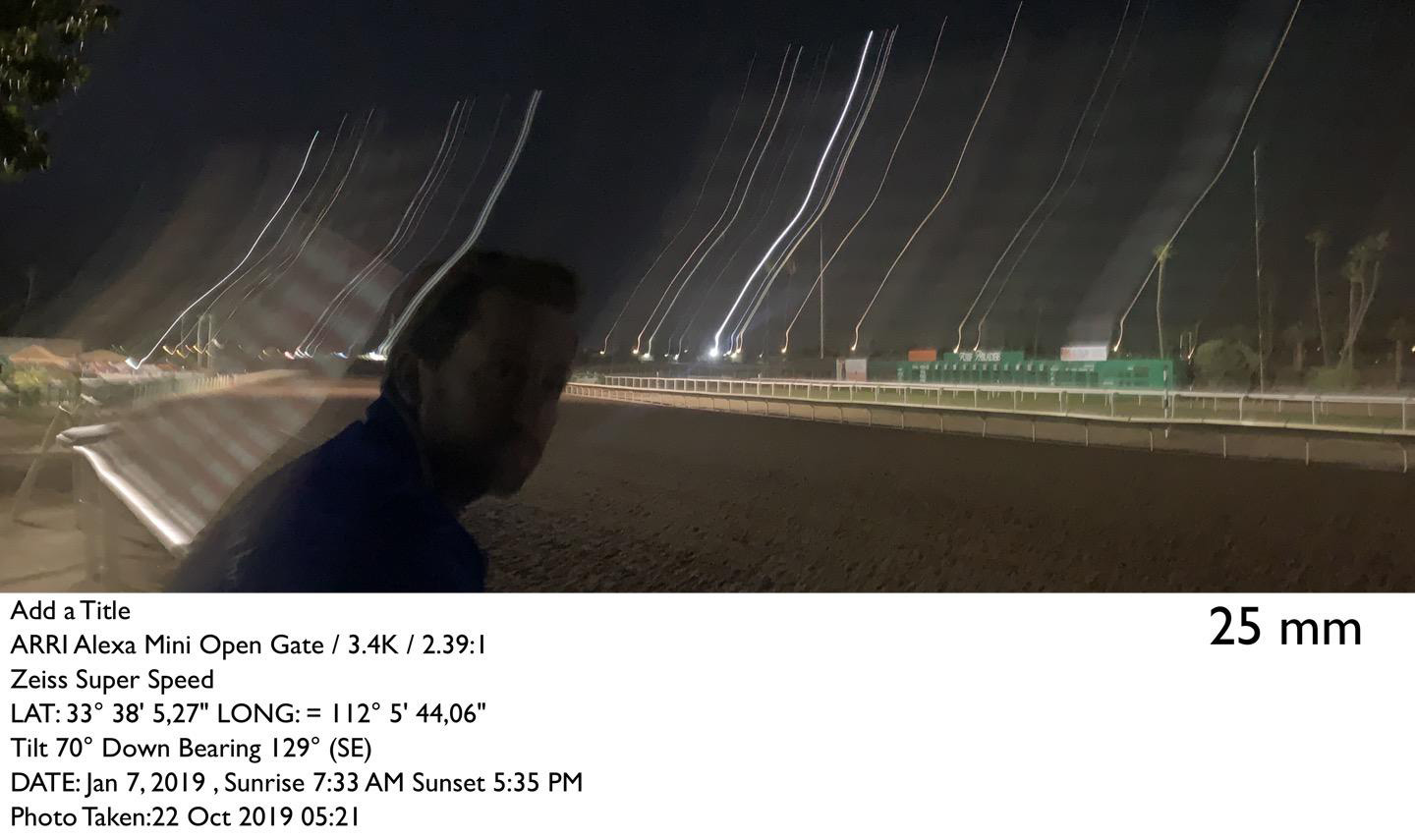

The jockeys back in Phoenix start their training before sunrise and the races take place in the late afternoon. In the middle of the day, because of the heat, I imagine, not much is happening on the track. We wanted to orbit around that and use these times as a visual metaphor to convey the characters’ moment in life.

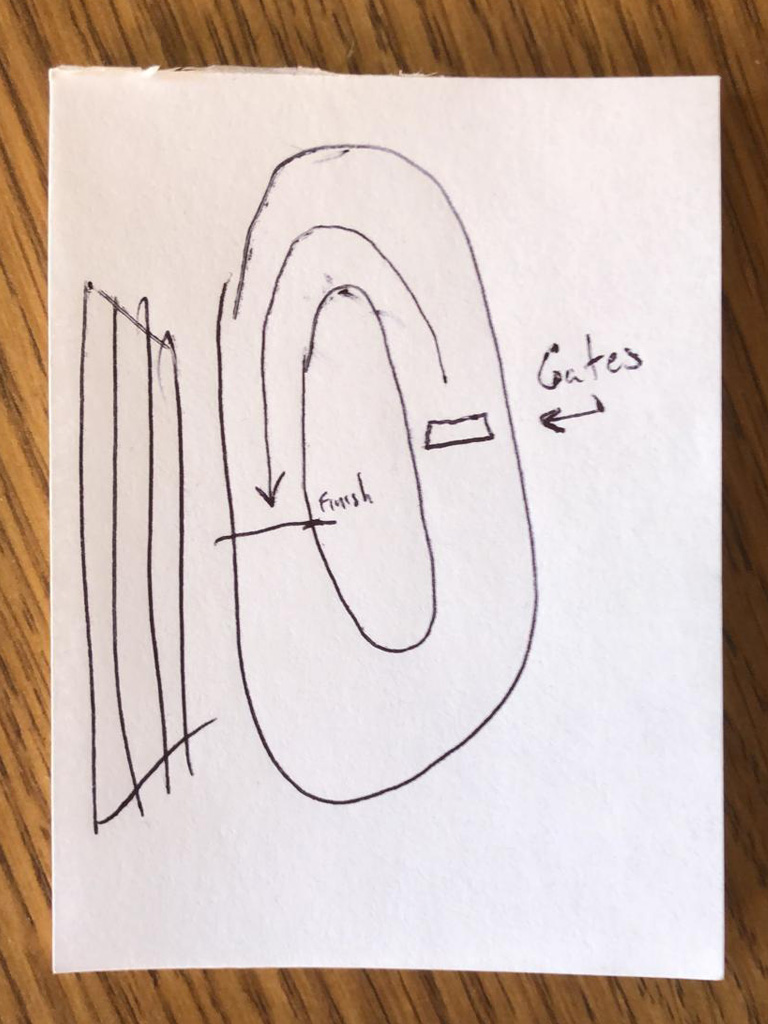

“Jockey” was filmed in 20 days. As the moments of light we chose to shoot the exteriors are very short, we usually rehearsed before the light got good. Due to having little time to shoot, we could not divide the scenes into different days. Overall, the decoupage was very simple, with lots of long shots where the camera follows the action, floating from one character to the next, with no coverings, which helps with light continuity when filming at these specific times. This language, in addition to helping narratively and bringing a documentary feel to the scripted scenes, allowed us to film everything in such a short time.

It was not possible to do sunrise and sunset on the same day because of the workload. So, when we wanted to film the sunrise, the rest of the day became interns. When we wanted the sunset, we usually combined it with the nocturnal ones.

The first thing Clint told me was that this was a movie about a jockey and not about horse racing. His father was a jockey and he felt that all the films on the subject over-glamorized this universe and adopted the point of view of the stands, the horse owners and punters. He wanted to make a movie about a jockey and all the physical and mental difficulties they face. They earn little money, break their entire body, need to control their own weight, wake up early every day and live with health problems caused by routines and falls.

To convey these ideas more effectively, we decided to make a point of view film. All we see is what Jackson sees, the viewer doesn’t see anything other than what Jackson is experiencing. Having a genius actor like Clifton was fundamental because the camera is on his face all the time and he delivers, every time, a lot of emotions without having to say a word.

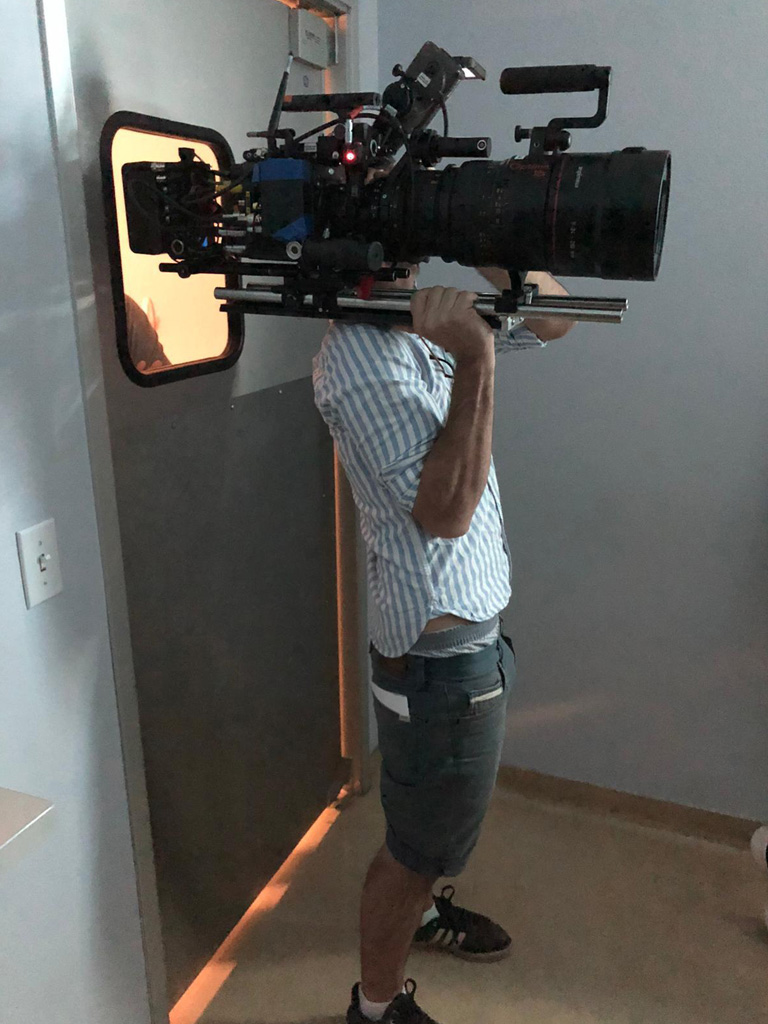

We didn’t film Clifton on top of the horses in any of the races. We wanted to be right next to him, running along with him. We filmed in the back of a pickup truck, with Clifton on a mock horse and me with the camera pressed to his face. The only difference between when he loses and when he wins, besides what you can see in the performance, is that when he loses they throw dirt in his face, which is what happens to the jockeys who are left behind. But it’s all there, there’s no horse and no CGI.

From the Zeiss kit, the lenses we used the most were the angled ones. Shooting a close-up with an angle lens allows you to be very close without losing the atmosphere. The 2.39 window combined with these lenses allowed us to always have more than one layer of information on the screen.

From the Zeiss kit, the lenses we used the most were the angled ones. Shooting a close-up with an angle lens allows you to be very close without losing the atmosphere. The 2.39 window combined with these lenses allowed us to always have more than one layer of information on the screen.

With this method, to avoid shadows from me or the camera, I generally tend to use a single light source. I avoid having any light source behind me, even if it’s a little to the sides, as I need freedom to move. I like to work with practical light. In this movie we had 2 60’s Skypanels and a set of Asteras. We rarely used any of these lights. The Gaffer, Elliot Travis, did a wonderful job of controlling the lights that were already on location. With a much greater thought of closing windows and turning off lights than adding new fonts. The cameras and lenses we have gave us freedom to work with less light. By letting natural light in through the window, we get quality and complexity that is difficult to achieve with cinema light. With an open window you got, for example, a more bluish light reaching the ground, because of the reflection of the sky, a part of the environment becomes greener because of the reflection of the trees, other part more yellow because of the yellow wall that has in front of the window, and so on… With a filtered reflector, you have a homogeneous and not very complex light. I prefer to just close windows and create contrasts that way.

I try never to have underexposed images. In general, I always try to have enough light somewhere in the frame so we can understand what’s going on, even if it’s a silhouette or just one side of the face. The contrast is usually brought about by the locations themselves. Working with single light sources allows you to better control contrast levels.

I was fortunate to have the Argentine Jonas Costa as a focus puller. He is a person of extreme skill and sensitivity, with whom I also worked on the movie “Mosquito”. We have a language connection, we don’t need to talk much. His ability to not anticipate the actors and always follow them is brilliant, even when we already know who is going to speak, as if he were trying to forget the script or rehearsals. It is as if he was there for the first time trying to react to the gestures, expressions, reactions and emotions of the characters, both those who speak and those who are listening.

We did a lot of the songwriting almost unconsciously. I remember witnessing from afar an informal conversation between Clifton and Moises, having fun and letting loose backstage. They already knew each other because they had worked together, when Moises was still a child, and it was an almost paternal relationship. I think this influenced me when filming them together in training with the camera outside the environments, observed from a slightly external point of view, to suggest a complicity between the two.

The choices of art and photography merge and add to each other. There was an exchange of suggestions. I visited the locations before the art director, Gui Marini, who is also Brazilian, arrived. We didn’t have a lot of money to interfere with the sets, so we chose everything together, considering the lighting conditions. The lamp, for example, was not part of the trailer’s original decor. The jockeys’ group therapy scene was practically created to take advantage of that room, which we discovered exploring the place and everyone fell in love even without having any scene from the script to shoot there.

COLOR CORRECTION

By Sergio Pasqualino Jr*

* Sergio Pasqualino has more than 20 years of experience as a colorist in Brazilian cinema, having participated in films such as “Cidade de Deus”, “Palíndromo”, “Árido Movie”, “Cidade dos Homens”, “Chega de Saudade”, “O Banheiro do Papa” and “Soundtrack”, in addition to commercials, music videos and the series “A Pedra do Reino” and “9 mm: São Paulo”. He works at Bleach Color Grading, a digital aesthetic treatment studio based in São Paulo and Barcelona.

COLOR CORRECTION

By Sergio Pasqualino Jr*

MINI BIO

Adolpho Veloso was a six-time finalist for the Brazilian Cinematography Association (ABC) award and won the trophy three times with the feature film “Mosquito” (2020), with the documentary “On Yoga: Arquitetura da Paz” (2017) and with the short “Diana” (2017). He is a finalist for the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) Spotlight Award for “Jockey” (2021), released at Sundance. He was also nominated three times for the Camerimage trophy with “On Yoga” and with the music videos “Miracle” (2019), by British singer Labrinth, and “Rastro de Pó”, by the Tagua Tagua project (Felipe Puperi). With “On Yoga”, he also won the IMAGO award, the International Federation of Cinematographers. In advertising, he has photographed commercials for brands such as Nike, Asics, Billboard, Tag Heuer and Mercedes. At festivals, he was awarded at the Mostra de València for “Mosquito” and at the Torino Underground Cinefest for “Rodantes” (2019). He also signed the direction of photography of nine short films, the features “El Perfecto David” (2021), “Tungstênio” (2018) and “Asco” (2015) and the series “Becoming Elizabeth (2022), launched by the north american channel Starz.